Laban’s notions of space are the most difficult to understand and to embody for many movement analysis students. Laban himself had to perform some mental gymnastics to capture the disappearing trace-forms of natural movement. Fortunately, he left a guidebook – Choreutics (aka – The Language of Movement).

Choreutics has always been my favorite book by Laban – but it is not an easy read. Consequently, I developed an “old school” correspondence course in 2016 –“Decoding Rudolf Laban’s Masterpiece, Choreutics.” Back by popular demand, this course takes readers on a guided tour of this fascinating book.

Based on an easy schedule, participants will read the Preface, Introduction, and first 12 chapters of Choreutics. A set of study questions will be provided for each reading assignment. When each reading assignment has been completed, participants will receive a commentary that I have prepared, providing background context and elaborating on Laban’s themes.

Think of this as a “great books” course designed to help movement specialists explore space with both body and mind. Find out more….

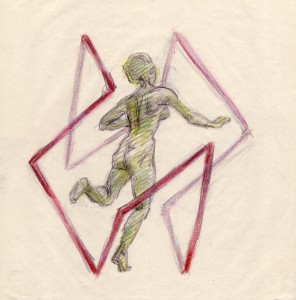

“We can understand all bodily movement as being a continuous creation of fragments of polyhedral forms,” Laban claimed. We set out to test this in the Prototypes project.

“We can understand all bodily movement as being a continuous creation of fragments of polyhedral forms,” Laban claimed. We set out to test this in the Prototypes project. In 2008, Professor Madeleine Scott and I ran a

In 2008, Professor Madeleine Scott and I ran a