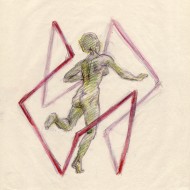

In 2008, Professor Madeleine Scott and I ran a choreutics-based research project at Ohio University. The project examined Laban’s claim that fragments of the choreutic forms (aka spatial scales and rings) compose a fundamental alphabet of human movement.

The examination had two parts. First, we set out to duplicate some of the choreutic forms that Laban represented as geometrical line drawings. Motion capture technology is able to produce a similar kind of record, for it captures the dancer’s movement as a linear tracery of light, allowing one to see the trace-forms of the dance without the dancer. … Read More