The division between science and art was much less marked in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and this made it possible for a polymath like Laban to know something about what was going on in each of these two intellectual cultures.

The division between science and art was much less marked in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and this made it possible for a polymath like Laban to know something about what was going on in each of these two intellectual cultures.

Here are a few examples. In his first career as a visual artist, Laban studied with Hermann Obrist in Munich. Before turning to art, Obrist had been a botanist. He drew on his scientific knowledge to generate stylized Art Nouveau designs of flora and fauna that moved increasingly towards abstraction, serving not only as a mentor to Laban but also to Vassily Kandinsky.

As Laban transitioned to a career in dance, he deepened his youthful interest in crystals just as crystallography was becoming a significant science – one that paved the road for later developments in physics. Laban was familiar with the writings and scientific illustrations of Ernst Haeckel, a natural scientist who discovered that animals, plants, and minerals are governed by the same principles of formation and movement.

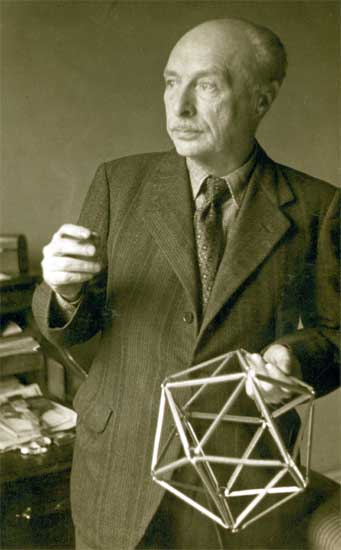

Archival traces of Laban’s interests also demonstrate his mathematical inclinations. The many drawings of Platonic and Aristotelian solids indicate that Laban was a gifted amateur geometer, conversant in symmetry operations. Drawings and letters show that Laban was also familiar with basic concepts of topology and speculative notions of the fourth dimension.

Beyond his obvious interests in art and dance, Laban was following developments in science and math. Moreover, he was using these to develop his own notions about the structure of human movement. Find out more in the next blogs.