Body language tends to single out isolated gestures and still poses for purposes of study. Then it attaches psychodynamic interpretations to these snapshot. Thus “arms folded over the chest” means a person is closed. Lifting and exposing the palm signals flirtation, rubbing the nose indicates disapproval, and so on.

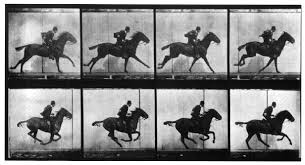

Body language isolates postures and gestures from the steam of ongoing movement in manner analogous to “instantaneous photographs,” such as those of Eadweard Muybridge. His photos recorded various moments in a series of actions. But because the recording was not continuous, each photographic image appears isolated, lifted out of the context before and after moments.

When these photos first appeared in the late 19th century, they were a revelation. They captured what normal vision could not perceive in rapid motion. But not everyone was impressed. The sculptor Rodin claimed that photography lies, “for in reality time does not stop.” Bergson the philosopher agreed. He admitted that a series of snapshots of an action can be mechanically animated to create an illusion of movement. But real movement is something else.

According to Bergson, it is not the “single snapshots we have taken once again along the course of change that are real; on the contrary, it is flux, the continuity of transition, it is change itself that is real.”

Real movement involves progressive development and change. Movement study aims to capture this process of change over time, to restore the context of before and after. Body language contents itself with the snapshot of “arms folded over the chest.” But, as Warren Lamb used to point out, there are many different ways to fold the arms – firmly and decisively, gradually, carefully, and so on. Surely meaning depends upon the before and after – not merely on one moment.