One challenging aspect of Laban’s Mastery of Movement is his description of many dramatic scenes meant to be embodied by the reader. These scenes involve multiple characters, various dramatic conflicts, and several changes in mood on the part of all the characters involved.

One challenging aspect of Laban’s Mastery of Movement is his description of many dramatic scenes meant to be embodied by the reader. These scenes involve multiple characters, various dramatic conflicts, and several changes in mood on the part of all the characters involved.

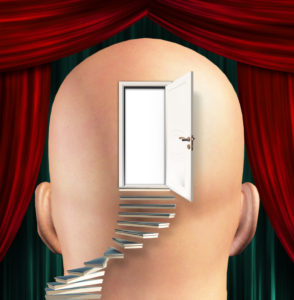

Laban wants the reader to get up and mime these scenes, thinking about how the body would be used, where movement would go in the space around the body, and what kind of efforts would appear and change. It’s a tall order, one requiring a rich imagination.

I’ve written elsewhere about the necessity of using imagination to bring Choreutic forms to life. But it is equally clear that using effort to embody various characters and dramatic situations requires imagination. Laban’s scenes demand great effort variation, but can easily stray into stereotypic or melodramatic choices. To avoid such regrettable diversion, Laban wants the reader to “think in terms of movement.”

Just as Laban was concerned to identify organic movements from place to place in the kinesphere, he was equally concerned to find natural sequences of effort change in the dynamosphere. His guidelines on effort patterning in Mastery are a bit sketchy, so I intend to integrate more detailed approaches for “thinking in terms of movement” in the forthcoming Octa seminar. To do so I’ll be drawing on several models of effort relationships that I uncovered during my research on unpublished theoretical materials in the Rudolf Laban Archive in England.

To find out more, participate in the spring correspondence course, “Mastering Rudolf Laban’s Mastery of Movement.”

In Mastery of Movement, Rudolf Laban invokes gods, goddesses, and demons in his discussions of the “chemistry of human effort.”

In Mastery of Movement, Rudolf Laban invokes gods, goddesses, and demons in his discussions of the “chemistry of human effort.” Laban’s life work was to create a rich palette of movement options from which a performer could draw. By the time he wrote Mastery of Movement, he had a lifetime of experience observing movement and working with dancers and actors, which he distilled into this intriguing work.

Laban’s life work was to create a rich palette of movement options from which a performer could draw. By the time he wrote Mastery of Movement, he had a lifetime of experience observing movement and working with dancers and actors, which he distilled into this intriguing work. I have been re-reading Laban’s autobiography in preparation for teaching

I have been re-reading Laban’s autobiography in preparation for teaching  Mastery of Movement is for body and effort what Choreutics is for space and shape – the most comprehensive treatment of Laban’s ideas in English. The book has an interesting history.

Mastery of Movement is for body and effort what Choreutics is for space and shape – the most comprehensive treatment of Laban’s ideas in English. The book has an interesting history. Long before diversity became a political issue, Warren Lamb was encouraging diversity in management teams. His model of diversity was not based on age, race, creed, or gender. Rather it was based on decision-making style.

Long before diversity became a political issue, Warren Lamb was encouraging diversity in management teams. His model of diversity was not based on age, race, creed, or gender. Rather it was based on decision-making style. In his observation and analysis of thousands of business executives,

In his observation and analysis of thousands of business executives,  Shortly after I completed my Laban Movement Analysis training (1976), Warren Lamb gave a short course at the Dance Notation Bureau. I had been thinking a lot about the relationship between movement and psychology, but in vague and hypothetical ways. What Lamb presented was much more concrete — it blew me away.

Shortly after I completed my Laban Movement Analysis training (1976), Warren Lamb gave a short course at the Dance Notation Bureau. I had been thinking a lot about the relationship between movement and psychology, but in vague and hypothetical ways. What Lamb presented was much more concrete — it blew me away. In 2011, I participated in a pilot study examining the validity of Movement Pattern Analysis profiles in predicting decision-making patterns. Although MPA has been used by senior business teams for over 50 years, its potential application to the study of military and political leaders has barely been tapped. The pilot study was the first test of this new area of application.

In 2011, I participated in a pilot study examining the validity of Movement Pattern Analysis profiles in predicting decision-making patterns. Although MPA has been used by senior business teams for over 50 years, its potential application to the study of military and political leaders has barely been tapped. The pilot study was the first test of this new area of application. The application of Movement Pattern Analysis in building teams was not the focus of my experiment with making basic profiles of undergraduate dance majors for a seminar on career development. However, I realized that an implicit team relationship clearly exists between student and teacher.

The application of Movement Pattern Analysis in building teams was not the focus of my experiment with making basic profiles of undergraduate dance majors for a seminar on career development. However, I realized that an implicit team relationship clearly exists between student and teacher.