More than any of his other books in English, Choreutics reveals Laban’s dual vision as a dance artist and movement scientist. The forthcoming course, “Decoding Choreutics,” examines Laban’s double vision from more than one angle.

For example, Choreutics and the whole fabric of Laban’s space harmony theory can be seen as a design source for dance. The various scales and “rhythmic circles” can be mined as abstract patterns for movement creation. In this sense, Choreutics is analogous to various design sources utilized by Art Nouveau artists at the turn of the 20th century.

The fin de siècle was a time when artistic and scientific circles overlapped. In their stylized renderings of natural forms, Art Nouveau artists drew upon scientific illustrations. A case in point is Ernst Haeckel’s Art Forms in Nature. Haeckel (1834-1919) was a biologist-philosopher whose beautiful illustrations of biological forms, ranging from microscopic creatures to sea life, plants, and animals, inspired the artists of his day.

One of the Art Nouveau artists who drew upon Haeckel’s illustrations was Hermann Obrist, with whom Laban studied in Munich. Originally trained as a botanist, Obrist the artist moved progressively from realistic depiction of natural forms to increasingly abstract and geometrical designs. Laban’s own geometricizing of the biomorphic curves of human movement in Choreutics follows a similar trajectory.

Led by the Art Nouveau movement, early 20th century artists were looking beyond the surface appearance of visual objects to reveal underlying patterns and organizing principles. With the advent of the atomic age, scientists were doing the same. Thus when Laban, the artist, turned his eyes to dance and human movement, he, too, was seeing double.

In the previous blog, I quoted Rudolf Laban’s characterization of choreutics as “the art, or the science” of movement study. Our postmodern perspective draws a hard line between art and science. But this was not the case when Laban was coming of age at the turn-of-the-century.

In the previous blog, I quoted Rudolf Laban’s characterization of choreutics as “the art, or the science” of movement study. Our postmodern perspective draws a hard line between art and science. But this was not the case when Laban was coming of age at the turn-of-the-century. Around 1913, Rudolf Laban abandoned his career as a visual artist to enter the field of dance. At the time, dance was a discipline defined more by what it lacked than by what it offered. Laban focused his energies on altering such conditions.

Around 1913, Rudolf Laban abandoned his career as a visual artist to enter the field of dance. At the time, dance was a discipline defined more by what it lacked than by what it offered. Laban focused his energies on altering such conditions. I have long been fascinated with the ritual of bowing in Japan. Clerks in a hotel bow when you enter the lobby. They bow when you finish checking in. Conductors bow when entering a train car. They bow again when exiting. Groups of friends, particularly if they are older, with bow deeply when parting.

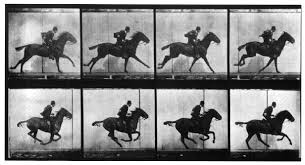

I have long been fascinated with the ritual of bowing in Japan. Clerks in a hotel bow when you enter the lobby. They bow when you finish checking in. Conductors bow when entering a train car. They bow again when exiting. Groups of friends, particularly if they are older, with bow deeply when parting. In the previous two blogs I have been contrasting body language and body movement. Body language tends to isolate still poses and particular gestures from the stream of ongoing bodily action and read fixed meanings into these snapshots. In so doing, the process of change, which is the essence of movement, disappears, as does the broader context of sequential actions. Body language treatises tend to present a stilted and mechanistic view of movement behavior. Perhaps this is why much of the study of body language promises to improve an individual’s ability to manage his/her image and manipulate others.

In the previous two blogs I have been contrasting body language and body movement. Body language tends to isolate still poses and particular gestures from the stream of ongoing bodily action and read fixed meanings into these snapshots. In so doing, the process of change, which is the essence of movement, disappears, as does the broader context of sequential actions. Body language treatises tend to present a stilted and mechanistic view of movement behavior. Perhaps this is why much of the study of body language promises to improve an individual’s ability to manage his/her image and manipulate others.