Artistic and scientific circles were not the only circles that overlapped in the fin de siècle period. European artists of the period were also involved in various secret spiritual societies that flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

For example, the painter Wassily Kandinsky was an ardent follower of Theosophy, one of the occult spiritual movements of the period, and one that was very attractive to artists. As religious historian Mircea Eliade notes, avant garde European artists “utilized the occult as a powerful weapon in their rebellion against the bourgeois establishment and its ideology.”

Novel spiritual practices were not merely a form of rebellion for the European avant garde. The occult revival also gave artists new ways to think about the nature of art as it moved beyond representation and symbolism toward formalism and abstraction. Kandinsky drew upon precepts of Theosophy, such as the quote above by Theosophy guru, Madame Blavatsky, to theorize a spiritual visual art composed of only form and color. By these means alone, Kandinsky wrote, the artist could “cause vibrations in the soul.”

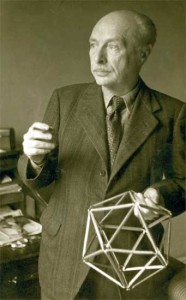

Laban was also attracted to the occult. During his career as a painter (1899- 1919), he supposedly associated with three esoteric groups: the Free Masons, the Ordo Templi Orientis, and the Rosicrucians. The extent of Laban’s involvement is a matter of speculation. Nevertheless, in Choreutics, his treatise on the geometry of human movement, Laban does acknowledge that his subject “necessitates a certain spiritual emphasis.”

What does this mean? Find out more in the correspondence course, “Decoding Choreutics,” beginning March 26.

Choreutics has always been my favorite book by Rudolf Laban, although it is by no means the most accessible of his writings. The text is prone to sudden jumps, from practical movement description to mystical metaphysics. Moreover, other mysteries surround this work.

Choreutics has always been my favorite book by Rudolf Laban, although it is by no means the most accessible of his writings. The text is prone to sudden jumps, from practical movement description to mystical metaphysics. Moreover, other mysteries surround this work. Beginning in March, MoveScape Center will offer a series of Red Thread courses centered on Rudolf Laban’s

Beginning in March, MoveScape Center will offer a series of Red Thread courses centered on Rudolf Laban’s  Moving rhythmically, in sync with others, is a peculiar human pleasure. “Muscular bonding” is the term William McNeill has coined to describe “the euphoric fellow feeling that prolonged and rhythmic muscular movement arouses among participants.”

Moving rhythmically, in sync with others, is a peculiar human pleasure. “Muscular bonding” is the term William McNeill has coined to describe “the euphoric fellow feeling that prolonged and rhythmic muscular movement arouses among participants.” I have long been fascinated with the ritual of bowing in Japan. Clerks in a hotel bow when you enter the lobby. They bow when you finish checking in. Conductors bow when entering a train car. They bow again when exiting. Groups of friends, particularly if they are older, with bow deeply when parting.

I have long been fascinated with the ritual of bowing in Japan. Clerks in a hotel bow when you enter the lobby. They bow when you finish checking in. Conductors bow when entering a train car. They bow again when exiting. Groups of friends, particularly if they are older, with bow deeply when parting. It is helpful to have a malleable

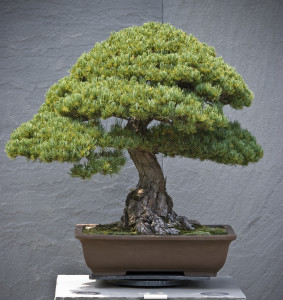

It is helpful to have a malleable  General space is a commodity not to be wasted in Japan. Heavily forested mountains cover most of the archipelago of islands. Flatland suitable for habitation and cultivation is precious. Wherever we have traveled in Japan, small rice fields, gardens, and orchards are sandwiched between a jumble of residential, commercial, and industrial buildings.

General space is a commodity not to be wasted in Japan. Heavily forested mountains cover most of the archipelago of islands. Flatland suitable for habitation and cultivation is precious. Wherever we have traveled in Japan, small rice fields, gardens, and orchards are sandwiched between a jumble of residential, commercial, and industrial buildings.