In his masterwork, Choreutics, Laban notes that “oscillations are the means of expression in the two arts, music and dance.” We found evidence supporting Laban’s observation in the Prototypes project.

In his masterwork, Choreutics, Laban notes that “oscillations are the means of expression in the two arts, music and dance.” We found evidence supporting Laban’s observation in the Prototypes project.

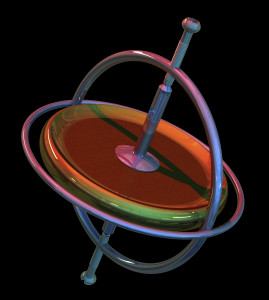

Of course, Laban has constructed his prototypic sequences as oscillations, shifting between opposite directions in space. The simplest pattern, the Dimensional Scale, oscillates between the cardinal directions. So the dancer reaches up, then down; opens the arm sideward, then reaches across the body; finally extends backward, then forward.

For Laban, however, there is more than one way to move up or down, or forward or backward. For the basic directions “follow one another with infinite variations, deflections, and deviations.” Thus upward movement can also veer forwards, or to the side, or backwards and across.

We found corroboration of Laban’s two observations in one of the improvisations recorded for the Prototypes project. The dancers were asked to play with the concept of stability and mobility. Marina Walchi’s spontaneous creation on this theme revealed an interesting pattern of oscillation. If she moved up, this was followed by a movement down. If across, by an opening action, and so on. The oscillation might occur after a sequence of directional changes, such as down-open-across, across-up, across-down. Nevertheless, an underlying vibratory pattern appeared.

In addition, the directional changes were not merely dimensional. Rather the shifting pattern was often deflected toward corners of the vertical, horizontal and sagittal planes or towards the diagonals.

Though only a single case, this example is intriguing. So here is a simple challenge – while talking with a friend, watch his/her hand gestures. Can you detect a pattern of directional reversal? Of deflections from the cardinal directions? Is it possible, as Laban asserted,that “between the harmonic components of music and dance there is not only an outward resemblance, but a structural congruity, which although hidden at first, can be investigated and verified, point by point?”

Laban moved into new Choreutic territory with five-rings, and consequently they are fascinating to embody. Primarily Laban built his space harmony scales around the cubic diagonals. But the peripheral and transverse five-rings that Cate Deicher and I will be teaching in the Advanced Space Harmony workshop are built around the planar diameters.

Laban moved into new Choreutic territory with five-rings, and consequently they are fascinating to embody. Primarily Laban built his space harmony scales around the cubic diagonals. But the peripheral and transverse five-rings that Cate Deicher and I will be teaching in the Advanced Space Harmony workshop are built around the planar diameters.

The aim of choreutic practice, according to Rudolf Laban, is “to stop the process of disintegrating into disunity.” In his view, bodily movement “can have a regenerating effect on our individual and social forms of life.”

The aim of choreutic practice, according to Rudolf Laban, is “to stop the process of disintegrating into disunity.” In his view, bodily movement “can have a regenerating effect on our individual and social forms of life.” In the Vaccination Theory of Education, students are led to believe that once they have “had” a subject, they are immune to it and need not take it again.

In the Vaccination Theory of Education, students are led to believe that once they have “had” a subject, they are immune to it and need not take it again. The Montreal event included a full morning of various presentations on applications of

The Montreal event included a full morning of various presentations on applications of  During the first week of June, I participated in unique collegial exchange with fourteen other movement analysts from the U.S., Canada, and France. Hosted by the Dance Department of the University of Quebec at Montreal, the seminar provided an opportunity for comparative and comprehensive study of two approaches to qualitative movement analysis:

During the first week of June, I participated in unique collegial exchange with fourteen other movement analysts from the U.S., Canada, and France. Hosted by the Dance Department of the University of Quebec at Montreal, the seminar provided an opportunity for comparative and comprehensive study of two approaches to qualitative movement analysis:  For many years, I have been puzzled by Laban’s emphasis on the cubic diagonals. He has embedded these oblique internal lines, which connect opposite corners of the cube, in his theories of both space and effort.

For many years, I have been puzzled by Laban’s emphasis on the cubic diagonals. He has embedded these oblique internal lines, which connect opposite corners of the cube, in his theories of both space and effort.

In his masterwork, Choreutics, Laban notes that “oscillations are the means of expression in the two arts, music and dance.” We found evidence supporting

In his masterwork, Choreutics, Laban notes that “oscillations are the means of expression in the two arts, music and dance.” We found evidence supporting  “We can understand all bodily movement as being a continuous creation of fragments of polyhedral forms,” Laban claimed. We set out to test this in the Prototypes project.

“We can understand all bodily movement as being a continuous creation of fragments of polyhedral forms,” Laban claimed. We set out to test this in the Prototypes project.