Laban Movement Analysis (LMA) requires thinking as well as moving. Whether one is working with performing arts majors or a more mixed population, most students have never thought about movement and its component parts. In this month’s series of blogs, I explore how to deal with some of the challenges of teaching LMA at the college level.

Besides providing rich movement experiences that highlight key features of movement (Body, Effort, Space, and Shape), it is vital to help students connect these experiences with meaning. One way is to start with general principles of the Laban system. I identify the following as key notions in Meaning in Motion: Introducing Laban Movement Analysis.

Movement is a process of change. Movement is not a position or even a series of positions. Movement is an uninterrupted flux.

The change is patterned and orderly. Body movement is dynamic and ephemeral. Nevertheless, laws of spatial sequencing and effort phrasing, along with the rhythms of stability/mobility and exertion/recuperation prevent human movement from being chaotic.

Human movement is intentional. Laban observed that human beings move to satisfy needs, both tangible and intangible. Movement reveals motivation.

The basic elements of human motion may be articulated and studied. Laban identified an “alphabet of the language of movement” that makes it possible to observe and analyze this psychophysical phenomenon.

Movement must be approached at multiple levels if it is to be properly understood. Movement is a dynamic process involving simultaneous changes in spatial positioning, bodily activation, and kinetic energy. Moreover, movement can be perceived from a variety of perspectives. It can simply be appreciated through immersion in the physical experience itself. It can be studied objectively, or it may be approached intellectually.

Find out more in the next blog.

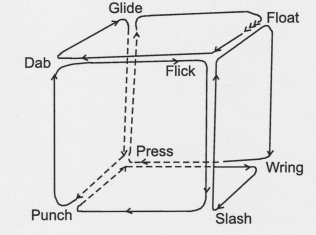

Then I began to find additional geometrical drawings among Laban’s writing about the psychological aspect of movement; that is, the dynamic qualities of kinetic energy that suggest the mover’s moods and intentions. Kinetic energy doesn’t manifest as a line in visible space in the same way that, say, the arm traces a line as it reaches upward. What kind of guy models effort phrases on three-dimensional Platonic solids?

Then I began to find additional geometrical drawings among Laban’s writing about the psychological aspect of movement; that is, the dynamic qualities of kinetic energy that suggest the mover’s moods and intentions. Kinetic energy doesn’t manifest as a line in visible space in the same way that, say, the arm traces a line as it reaches upward. What kind of guy models effort phrases on three-dimensional Platonic solids?

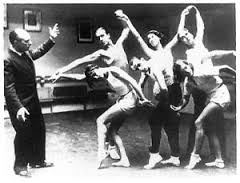

As for elaboration, Laban has a reputation for leaving this to students and colleagues. Notation is the classic example. Laban generated the basic format, but it took the painstaking work of Albrecht Knust, Ann Hutchinson Guest, and others to make it a practical recording system. Possessed by a creative energy, Laban developed a reputation for rushing ahead with ideas and leaving the execution to others. His protege Kurt Jooss complained that Laban never gave concrete answers. Associate Valerie Preston-Dunlop observed that Laban preferred to leave “the foundations of his work” in a “state of liquidity.” Geraldine Stephenson concurs, “Laban did not like the words: system, method, or technique.”

As for elaboration, Laban has a reputation for leaving this to students and colleagues. Notation is the classic example. Laban generated the basic format, but it took the painstaking work of Albrecht Knust, Ann Hutchinson Guest, and others to make it a practical recording system. Possessed by a creative energy, Laban developed a reputation for rushing ahead with ideas and leaving the execution to others. His protege Kurt Jooss complained that Laban never gave concrete answers. Associate Valerie Preston-Dunlop observed that Laban preferred to leave “the foundations of his work” in a “state of liquidity.” Geraldine Stephenson concurs, “Laban did not like the words: system, method, or technique.”