In his early days as a management consultant, Warren Lamb frequently helped client companies appoint employees. He would be called in to interview a short-list of people being considered for a position. His assessment, based upon the candidates’ movement patterns, would be used, in addition to other measures, to find the right person for the job.

In his early days as a management consultant, Warren Lamb frequently helped client companies appoint employees. He would be called in to interview a short-list of people being considered for a position. His assessment, based upon the candidates’ movement patterns, would be used, in addition to other measures, to find the right person for the job.

Lamb was aware that some people simply come across better in an interview than others. They are able to manage the image they create adroitly, in part through their nonverbal behaviors. The candidate can assume a self-confident posture and make the firm gestures of a strong leader for the duration of the interview – without actually being a strong and confident leader.

Thus Lamb had to be able to discern artificial movement behaviors, temporarily put on to create a good impression, from actions that were genuine and truly characteristic of the individual.

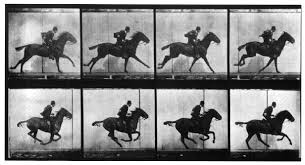

To do so, he had to shift his analysis beyond static poses and isolated gestures and focus on dynamic actions. In carefully observing the ongoing stream of movement that accompanies speech, Lamb made an important discovery. He began to notice that some gestures merged into action involving the whole body, and vice versa. These phrases of posture-gesture merger occurred spontaneously and naturally as coherent physical expressions. Lamb had found the key to discerning genuine and characteristic actions from “body language” that can be faked.

As he notes, “We can relatively easily change gestures… we can easily work on bad posture. But it seems that if we cannot change the quality of movement at the point where gestures merge into posture, or vice versa, then it has a particular significance.”

In the next blog, I will discuss the particular significance of the merging of posture and gesture.

In his unpublished papers Laban also observed, “inner becomes outer and outer becomes inner.” That is, movement not only reflects what a person is thinking and feeling, it also affects one’s inner psychological state.

In his unpublished papers Laban also observed, “inner becomes outer and outer becomes inner.” That is, movement not only reflects what a person is thinking and feeling, it also affects one’s inner psychological state.