One thing many readers have difficulty grappling with in Choreutics is Laban’s geometricizing of the dancer’s space. Laban’s first career as a visual artist helps to explain this use of geometry.

One thing many readers have difficulty grappling with in Choreutics is Laban’s geometricizing of the dancer’s space. Laban’s first career as a visual artist helps to explain this use of geometry.

Visual artists have employed geometrical schemes to capture human proportion and motion since Egyptian times. These schemes have differed. The Egyptians used a flat grid; Byzantine artists employed a series of concentric circles; and medieval artists superimposed ornamental shapes like triangles and stars on the human body to set contours and directions of movement, albeit in a highly stylized way.

However, as I explain in The Harmonic Structure of Movement, Music, and Dance, the use of geometry to realistically depict a three-dimensional moving body reached its apex in the Renaissance in the work of two artists: Albrecht Durer and Leonardo da Vinci. Both developed geometrical schemes that became part of academic art training and, despite the demise of the great European art academies, are still used today.

In Durer’s approach, simple solid shapes such as cubes, are superimposed on parts of a posed figure. These simple shapes can be tilted, rotated, and redrawn in proper proportion to deal with the visible changes in proportion that occur when the body is posed in various positions.

Leonardo’s scheme focuses more on bodily motion. He reasoned that the circle is the correct pattern of movement of the human body. These circles become visible in the circling of the body around its own center and the limbs around their joints.

Laban draws on both schemes in his theorizing of the dancer’s space. Find out more in the forthcoming Tetra course, “Decoding Laban’s Choreutics.”

In the previous blog, I quoted Rudolf Laban’s characterization of choreutics as “the art, or the science” of movement study. Our postmodern perspective draws a hard line between art and science. But this was not the case when Laban was coming of age at the turn-of-the-century.

In the previous blog, I quoted Rudolf Laban’s characterization of choreutics as “the art, or the science” of movement study. Our postmodern perspective draws a hard line between art and science. But this was not the case when Laban was coming of age at the turn-of-the-century. Choreutics is in many ways a straight-forward presentation of Laban’s movement theories. However, more than any of Laban’s other books in English, Choreutics is colored by Laban’s worldview.

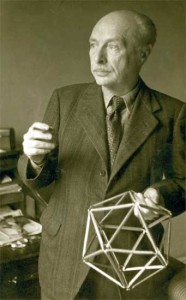

Choreutics is in many ways a straight-forward presentation of Laban’s movement theories. However, more than any of Laban’s other books in English, Choreutics is colored by Laban’s worldview. Around 1913, Rudolf Laban abandoned his career as a visual artist to enter the field of dance. At the time, dance was a discipline defined more by what it lacked than by what it offered. Laban focused his energies on altering such conditions.

Around 1913, Rudolf Laban abandoned his career as a visual artist to enter the field of dance. At the time, dance was a discipline defined more by what it lacked than by what it offered. Laban focused his energies on altering such conditions.

Choreutics has always been my favorite book by Rudolf Laban, although it is by no means the most accessible of his writings. The text is prone to sudden jumps, from practical movement description to mystical metaphysics. Moreover, other mysteries surround this work.

Choreutics has always been my favorite book by Rudolf Laban, although it is by no means the most accessible of his writings. The text is prone to sudden jumps, from practical movement description to mystical metaphysics. Moreover, other mysteries surround this work. Beginning in March, MoveScape Center will offer a series of Red Thread courses centered on Rudolf Laban’s

Beginning in March, MoveScape Center will offer a series of Red Thread courses centered on Rudolf Laban’s  The wintery month of January is named after the Roman god Janus. Janus had two faces, one that looked back and one that looked forward. Similarly, this time of year invites introspection – reflection on things past and anticipation of things yet to be. In honor of Janus, I look back and forward.

The wintery month of January is named after the Roman god Janus. Janus had two faces, one that looked back and one that looked forward. Similarly, this time of year invites introspection – reflection on things past and anticipation of things yet to be. In honor of Janus, I look back and forward. We have no sensory mechanism for perceiving time. And yet we are aware of time as a phenomenon closely related to movement. On some uncanny occasions, time appears to stand still. But mostly time seems to move like a dancer – sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly.

We have no sensory mechanism for perceiving time. And yet we are aware of time as a phenomenon closely related to movement. On some uncanny occasions, time appears to stand still. But mostly time seems to move like a dancer – sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly.