Once upon a time, dance was a local phenomenon. Because dance was rooted in the community, Rudolf Laban hypothesized that “an observer of tribal and national dances can gain information about the states of mind or traits of character cherished and desired within the particular community.” This is because “these dances show the effort range cultivated by social groups living in a definite milieu.”

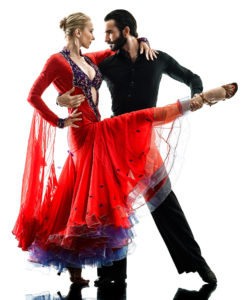

Globalization is changing this. Popular dance forms in particular move across borders with remarkable speed. Tango, salsa, competitive ballroom dance, and hip-hop – to name just a few – are now performed around the world, often by social groups different in class, race, and temperament from the milieu in which the dance originated.

Nowadays, dancers form transnational sodalities. Sodalities are non-kin groups organized for a specific purpose. This has led Jonathan Marion to argue that competitive ballroom dancers, for example, are quite literally – “a ‘tribe’ of dancers with a collective identity, the shared experience of a translocal ballroom culture of practice and competition, which exists side-by-side with members’ own national culture.”

Culture, of course, is deeply embedded in bodily practices absorbed from birth and often buried below conscious awareness. Dance is a conscious bodily practice, however. It must be learned. Learning dances that originated elsewhere expands not only movement repertoire but movement identity.

In a world where many would strengthen the divisions between nations and peoples, let’s keep dancing!