Polar triangles, axis and girdle scales, primary scales, and the A and B scales – these were the Laban prototypes we wanted to study. Thus the research project began with a crash course in space harmony for three Ohio University dance faculty (Travis Gatling, Tresa Randall, and Marina Walchi).

Polar triangles, axis and girdle scales, primary scales, and the A and B scales – these were the Laban prototypes we wanted to study. Thus the research project began with a crash course in space harmony for three Ohio University dance faculty (Travis Gatling, Tresa Randall, and Marina Walchi).

We only had three days to prepare our performers (all relative newcomers to Laban theory) for the motion capture/videotaping session. We wanted the dancers not only to remember the prototypic sequences but also to perform them well. Consequently, each morning and afternoon rehearsal began with a Bartenieff Fundamentals warm up as an inroad for connecting body and space.

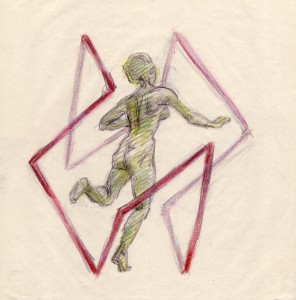

As the week proceeded, the dancers were introduced to the three geographies of the kinesphere – the octahedron, the cube, and the icosahedron. They learned the dimensional and diagonal scales as Laban’s models of stable and mobile trajectories respectively. They embodied the cardinal planes, tracing the peripheral edges and central diameters. They were introduced to transverse movement and learned the A and B scales.

We then moved on to prototypes drawing on the more subtle “deflected directions.” Thus the dancers were taught the polar triangles, axis and girdle scales, and finally the most complex and counter-intuitive primary scales.

In the final afternoon rehearsal, we jointly decided who would perform each choreutic sequence and worked on fine-tuning the phrasing. The acid test would start the following morning, when we gathered in the campus TV studio for the motion capture and video recording session.

In 2008, Professor Madeleine Scott and I ran a

In 2008, Professor Madeleine Scott and I ran a

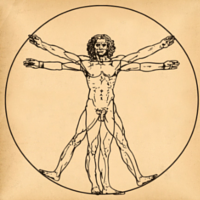

In the preface to Choreutics, Laban defines “choreography” as the “designing or writing of circles.” While we use the word today to designate composing dances, Laban was obviously familiar with the origins of the term, which come from two Greek words – khoros and graphein.

In the preface to Choreutics, Laban defines “choreography” as the “designing or writing of circles.” While we use the word today to designate composing dances, Laban was obviously familiar with the origins of the term, which come from two Greek words – khoros and graphein. In Choreutics, Laban mentions in passing a dizzying array of subjects —

In Choreutics, Laban mentions in passing a dizzying array of subjects — One thing many readers have difficulty grappling with in Choreutics is Laban’s geometricizing of the dancer’s space. Laban’s first career as a visual artist helps to explain this use of geometry.

One thing many readers have difficulty grappling with in Choreutics is Laban’s geometricizing of the dancer’s space. Laban’s first career as a visual artist helps to explain this use of geometry. In the previous blog, I quoted Rudolf Laban’s characterization of choreutics as “the art, or the science” of movement study. Our postmodern perspective draws a hard line between art and science. But this was not the case when Laban was coming of age at the turn-of-the-century.

In the previous blog, I quoted Rudolf Laban’s characterization of choreutics as “the art, or the science” of movement study. Our postmodern perspective draws a hard line between art and science. But this was not the case when Laban was coming of age at the turn-of-the-century. Choreutics is in many ways a straight-forward presentation of Laban’s movement theories. However, more than any of Laban’s other books in English, Choreutics is colored by Laban’s worldview.

Choreutics is in many ways a straight-forward presentation of Laban’s movement theories. However, more than any of Laban’s other books in English, Choreutics is colored by Laban’s worldview. Around 1913, Rudolf Laban abandoned his career as a visual artist to enter the field of dance. At the time, dance was a discipline defined more by what it lacked than by what it offered. Laban focused his energies on altering such conditions.

Around 1913, Rudolf Laban abandoned his career as a visual artist to enter the field of dance. At the time, dance was a discipline defined more by what it lacked than by what it offered. Laban focused his energies on altering such conditions.