Laban personifies each of the eight basic actions in Mastery of Movement. He characterizes Floating (all indulging qualities of Weight, Time, and Space) as the Goddess and Punching (all fighting effort qualities) as the Demon. He goes on to note that it will not be difficult for the actor or dancer to depict these characters, for we “remember the age-old symbolism of love’s soft floating movements, and of the violent and abrupt movements of hatred.”

During the recent MoveScape Center Mastery of Movement  correspondence course, Rebecca Nordstrom created a sequence of basic actions and imagined this movement sequence as a scenario involving the Demon and the Goddess. It is a beautiful example of how imagination can bring Laban’s effort theories to life.

correspondence course, Rebecca Nordstrom created a sequence of basic actions and imagined this movement sequence as a scenario involving the Demon and the Goddess. It is a beautiful example of how imagination can bring Laban’s effort theories to life.

Becky has graciously allowed me to share her scenario….

Scale of moods order: Punch, slash, wring, press, glide, dab, flick, float.

A demon looks at the large oblong object that mysteriously appeared in his lair. First, he strikes it with his fist, punching repeatedly to try to break it open. He then slings it violently and repeatedly around the room sending it crashing into the walls, floor, and ceiling (slashing). When that doesn’t work, he grabs it in his hands and tries to twist it open with great force (wringing). Lastly, he leans against it with all his force trying to crush it (pressing). Exhausted, he collapses into a heap and falls asleep.

Out of a hole at one end of the object a veiled figure slowly, gently and steadily emerges (gliding). Once free of the object the figure quickly but gently pokes at the surrounding veil with long delicate fingers and toes (dabbing). Once loosened, the veil is gently but quickly tossed aside with flicking gestures.

Now completely free of the veil, the figure begins to spread its wings and gently, delicately rises. As the butterfly goddess knew, she was only able to emerge from her chrysalis cage with the help of the unsuspecting demon. She hovers over his sleeping body to whisper her thanks before floating gently out of his lair and into the bright sunshine.

A Movement Pattern Analysis profile reflects how an individual balances Assertion (the exertion of tangible movement effort to make something happen) with Perspective (positioning oneself to get a better view of the situation). In the pilot study group, some individuals emphasized Assertion, while others favored Perspective.

A Movement Pattern Analysis profile reflects how an individual balances Assertion (the exertion of tangible movement effort to make something happen) with Perspective (positioning oneself to get a better view of the situation). In the pilot study group, some individuals emphasized Assertion, while others favored Perspective. Over the past six years, I have been part of an interdisciplinary research team testing Movement Pattern Analysis (MPA). The team consists of movement analysts, political scientists, and psychologists. We have been comparing the Movement Pattern Analysis profiles of a participant group of military officers with their performance on a set of decision-making tasks completed in a laboratory situation. Our aim is to assess how well their MPA profiles correlate with their decision-making behaviors in the lab.

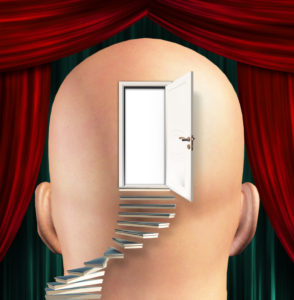

Over the past six years, I have been part of an interdisciplinary research team testing Movement Pattern Analysis (MPA). The team consists of movement analysts, political scientists, and psychologists. We have been comparing the Movement Pattern Analysis profiles of a participant group of military officers with their performance on a set of decision-making tasks completed in a laboratory situation. Our aim is to assess how well their MPA profiles correlate with their decision-making behaviors in the lab. Movement Pattern Analysis is based on the premise that patterns of body movement reflect cognitive processes involved in making decisions. This premise usually is met with skepticism, for at the level of popular consciousness, mind and body are still separate entities.

Movement Pattern Analysis is based on the premise that patterns of body movement reflect cognitive processes involved in making decisions. This premise usually is met with skepticism, for at the level of popular consciousness, mind and body are still separate entities.

One challenging aspect of Laban’s Mastery of Movement is his description of many dramatic scenes meant to be embodied by the reader. These scenes involve multiple characters, various dramatic conflicts, and several changes in mood on the part of all the characters involved.

One challenging aspect of Laban’s Mastery of Movement is his description of many dramatic scenes meant to be embodied by the reader. These scenes involve multiple characters, various dramatic conflicts, and several changes in mood on the part of all the characters involved. In Mastery of Movement, Rudolf Laban invokes gods, goddesses, and demons in his discussions of the “chemistry of human effort.”

In Mastery of Movement, Rudolf Laban invokes gods, goddesses, and demons in his discussions of the “chemistry of human effort.” Laban’s life work was to create a rich palette of movement options from which a performer could draw. By the time he wrote Mastery of Movement, he had a lifetime of experience observing movement and working with dancers and actors, which he distilled into this intriguing work.

Laban’s life work was to create a rich palette of movement options from which a performer could draw. By the time he wrote Mastery of Movement, he had a lifetime of experience observing movement and working with dancers and actors, which he distilled into this intriguing work.