There is a well-known marketing adage – no one wants a bar of soap. Customers want to be clean, have soft skin, or smell nice. By extension, no one wants a Laban Movement Analysis. Instead, our customers want to dance better, find a way to stop back pain, or gain insight into self and other.

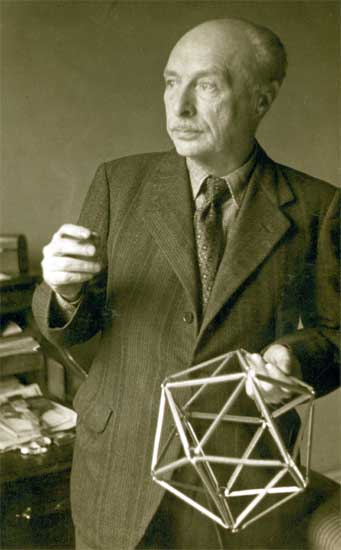

Rudolf Laban called movement “man’s magic mirror.” He saw that movement reflects motivations, thoughts, and feelings. He drew analogies between the mastery of movement and the mastery of self.

In the Laban Movement Analysis world to date, however, there are only three outstanding applications of movement analysis that link movement and meaning: the Kestenberg Movement Profile (nonverbal aspects of human development and parent-child interactions), Choreometrics (folk dance style, work movement, and climate), and Movement Pattern Analysis (decision making patterns of self and others).

Several factors make these applications of movement analysis outstanding:

1) Human movement behavior is observed and coded systematically,

2) Movement data is linked to meaning in ways that are both explicit and transparent,

3) The interpretations of movement behavior derived from these applications of movement analysis are accessible and make sense to the lay public.

Movement analysis is most valuable when it yields benefits. Find out how Movement Pattern Analysis can benefit you at the upcoming Embodied Decision Making course on Labor Day weekend.