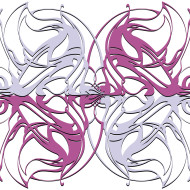

Rudolf Laban was crazy about symmetry. His first career as a visual artist spanned the period from 1899 to 1919. During this period, Art Nouveau, with its focus on two-dimensional pattern, was in fashion. Surviving works show that Laban worked in this style and was familiar with symmetry operations as a means of generating pattern.

When Laban turned his artist’s eyes to dance, he realized the power of symmetry for generating three-dimensional patterns. Virtually all his Choreutic forms and scales are highly symmetrical.… Read More