Laban’s assertion that human movement has a harmonic structure analogous to music has vexed scholars ranging from Suzanne Langer to Lincoln Kirstein. In general, the notion of movement harmony has been viewed as an artifact of Laban’s mystical philosophy. In my view, however, harmony is a useful theoretical construct for explaining certain empirical aspects of human movement.

Laban’s assertion that human movement has a harmonic structure analogous to music has vexed scholars ranging from Suzanne Langer to Lincoln Kirstein. In general, the notion of movement harmony has been viewed as an artifact of Laban’s mystical philosophy. In my view, however, harmony is a useful theoretical construct for explaining certain empirical aspects of human movement.

For example, aestheticians have categorized the arts as either spatial or temporal. However, dance is a hybrid art. The dance unfolds in both space and time, both for the dancer and for the observer. By extension, the same holds true for all human movement. In reality, space and time combine.

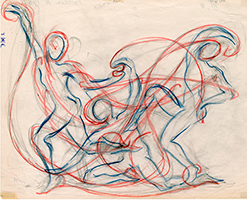

For analytical purposes, Laban divided his theory in two parts – Choreutics addresses the spatial aspects of movement while Eukinetics deals with temporal factors. Yet Laban freely admits this is an artificial division, for in reality spatial form and dynamic stress “are entirely inseparable from each other.” And this is where the notions of harmony comes in.

Harmony brings things that are different into accord by allowing parts to be related to the whole or to one another. In normal human movement, body, effort, and space cohere in meaningful action. Unless disease or injury interrupts this coherence, voluntary body movement occurs automatically, without constant, conscious intervention.

Human movement is a psychophysical phenomenon, an integration of mind and body. This is its most remarkable feature. While we cannot fully explain the mechanisms through which this integration occurs, it is a fact, not a fiction.

“Harmony” is the term Laban chose for describing the seemingly natural coherence of body, space, and effort. He envisioned movement study as an integration of art and science, analysis and synthesis. The study of movement harmony was meant to “stop the process of disintegrating into disunity.” For in Laban’s eyes, movement “with all its significance for the human personality, can have regenerating effect on our individual and social forms of life.”

The forthcoming college text, Meaning in Motion: Introducing Laban Movement Analysis incorporates discussion of Laban’s fundamental notions of movement harmony.

In the preface to his book, Choreutics, Laban links his modern studies of movement to Pythagorean mathematics, notably musical scales and the “harmonic relations” of geometrical forms such as the right triangle and circle. Laban appears to have coined the term Choreutics from two Greek root words: “khoreia” (dancing in unison) and “eu” (beautiful, harmonious).

In the preface to his book, Choreutics, Laban links his modern studies of movement to Pythagorean mathematics, notably musical scales and the “harmonic relations” of geometrical forms such as the right triangle and circle. Laban appears to have coined the term Choreutics from two Greek root words: “khoreia” (dancing in unison) and “eu” (beautiful, harmonious). The arts are sometimes divided into

The arts are sometimes divided into