Another example of Laban’s double vision is his concept of the kinesphere and dynamosphere as dual domains of human movement. To represent both domains, Laban utilizes the cube.

With regard to the kinesphere, Laban uses the cube quite literally. Its corners, edges, and internal diagonals serve as a kind of longitude and latitude for mapping movement in the space around the dancer’s body.

With regard to the dynamosphere, Laban uses the cube formally to represent patterns of effort change. This shift in how the model should be interpreted is complicated further by Laban’s use of direction symbols to stand for effort qualities and combinations.

When Laban wrote Choreutics in 1938-39, the effort symbols had not yet been created. Consequently, his dual use of direction symbols to stand in for effort obscures the discussion, but not entirely.

To decode the models discussed in Chapters 3, 6, and 9, it is only necessary to translate the direction symbols into effort qualities and combinations. Once this is done, Laban’s discussion of dynamospheric patterns becomes clear.

Want more keys? Register for the correspondence course, “Decoding Laban’s Choreutics,” beginning March 26.

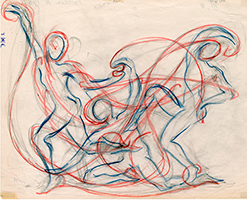

One thing many readers have difficulty grappling with in Choreutics is Laban’s geometricizing of the dancer’s space. Laban’s first career as a visual artist helps to explain this use of geometry.

One thing many readers have difficulty grappling with in Choreutics is Laban’s geometricizing of the dancer’s space. Laban’s first career as a visual artist helps to explain this use of geometry. In the previous blog, I quoted Rudolf Laban’s characterization of choreutics as “the art, or the science” of movement study. Our postmodern perspective draws a hard line between art and science. But this was not the case when Laban was coming of age at the turn-of-the-century.

In the previous blog, I quoted Rudolf Laban’s characterization of choreutics as “the art, or the science” of movement study. Our postmodern perspective draws a hard line between art and science. But this was not the case when Laban was coming of age at the turn-of-the-century. Choreutics is in many ways a straight-forward presentation of Laban’s movement theories. However, more than any of Laban’s other books in English, Choreutics is colored by Laban’s worldview.

Choreutics is in many ways a straight-forward presentation of Laban’s movement theories. However, more than any of Laban’s other books in English, Choreutics is colored by Laban’s worldview.

Laban’s assertion that human movement has a harmonic structure analogous to music has vexed scholars ranging from Suzanne Langer to Lincoln Kirstein. In general, the notion of movement harmony has been viewed as an artifact of Laban’s mystical philosophy. In my view, however, harmony is a useful theoretical construct for explaining certain empirical aspects of human movement.

Laban’s assertion that human movement has a harmonic structure analogous to music has vexed scholars ranging from Suzanne Langer to Lincoln Kirstein. In general, the notion of movement harmony has been viewed as an artifact of Laban’s mystical philosophy. In my view, however, harmony is a useful theoretical construct for explaining certain empirical aspects of human movement.

In the preface to his book, Choreutics, Laban links his modern studies of movement to Pythagorean mathematics, notably musical scales and the “harmonic relations” of geometrical forms such as the right triangle and circle. Laban appears to have coined the term Choreutics from two Greek root words: “khoreia” (dancing in unison) and “eu” (beautiful, harmonious).

In the preface to his book, Choreutics, Laban links his modern studies of movement to Pythagorean mathematics, notably musical scales and the “harmonic relations” of geometrical forms such as the right triangle and circle. Laban appears to have coined the term Choreutics from two Greek root words: “khoreia” (dancing in unison) and “eu” (beautiful, harmonious).