When the dancer Rudolf Laban began to study work movement in British factories, two concerns predominated. The first was efficiency; the second was fatigue. By the 1940s, of course, there were laws governing the length of the workday and providing additional protection for the health and safety of workers. Nevertheless, repetitive activity of any sort is tiring. Human beings are not machines. We cannot repeat any motion endlessly without the need for variation.

When the dancer Rudolf Laban began to study work movement in British factories, two concerns predominated. The first was efficiency; the second was fatigue. By the 1940s, of course, there were laws governing the length of the workday and providing additional protection for the health and safety of workers. Nevertheless, repetitive activity of any sort is tiring. Human beings are not machines. We cannot repeat any motion endlessly without the need for variation.

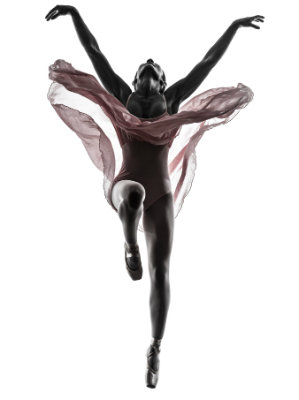

In turning his dancer’s eyes to repetitive labor, Laban identified a basic rhythm. He recognized that there is some form of preparation, followed by a more intense phase of effortful exertion, and concluding with some form of recovery and recuperation. Laban found that the concluding phase of recuperation was often overlooked in the “efficient” ways of working prescribed by the time and motion specialists.

Laban took a different approach. As I describe in Meaning in Motion, he believed that recuperation did not mean passive rest. Rather he looked for effective ways for a worker to recover actively through effort variation. For example, if the job function required downward pressure, Laban introduced an upward movement with released pressure somewhere in the movement phrase. This allowed him to build recuperative actions into the job function itself.

Fatigue remains a problem in the workplace today, despite the fact that jobs are increasingly sedentary. Nevertheless, the importance of building active recuperation into the rhythm of the workday remains a concern. Find out more in the following blog.

The arts are sometimes divided into

The arts are sometimes divided into

Space isn’t empty for architects. Like a surgical suture, space connects a building with the other objects in the environment. Without empty space, an architectural design has no context. What isn’t there allows us to see what is there.

Space isn’t empty for architects. Like a surgical suture, space connects a building with the other objects in the environment. Without empty space, an architectural design has no context. What isn’t there allows us to see what is there. In his unpublished papers Laban also observed, “inner becomes outer and outer becomes inner.” That is, movement not only reflects what a person is thinking and feeling, it also affects one’s inner psychological state.

In his unpublished papers Laban also observed, “inner becomes outer and outer becomes inner.” That is, movement not only reflects what a person is thinking and feeling, it also affects one’s inner psychological state.