In the summer of 1975, I left the Nikolai-Louis Studio, walked across Union Square to the Dance Notation Bureau, and declared I was interested in the Effort/Shape Program.

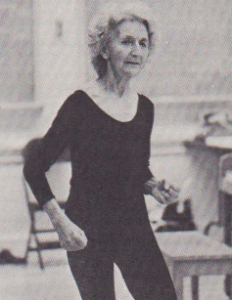

I was ushered in to see Irmgard Bartenieff, a delicate elderly German lady who had worked directly with Rudolf Laban. She was guiding spirit of the Effort/Shape program. I don’t remember exactly what we talked about, but Irmgard was open and encouraging. I became her student, then her assistant, and eventually a fellow faculty member.

After her death, when I left New York and found myself on my own with no Laban colleagues handy, I really missed Irmgard. Then I began to appreciate fully the scope of her knowledge and the positive impact of who she was and her whole way of being in the world.

Consequently, I am delighted that Irmgard Bartenieff’s archives have a home now at the University of Maryland library. I am looking forward to the upcoming Symposium on November 10th, when those influenced by Bartenieff will share their reminiscences. This event, organized by archivist Susan L. Wiesner, launches an exhibit in the Performing Arts Library gallery that follows Irmgard’s path through her professional life. And what a career – dancer, Laban student, Labanotator, physical therapist, dance therapist, Effort/Shape guru, teach, author, and dance ethnographer. She was a living example of the many ways movement study can be applied. Thus the title of my Symposium talk – “Irmgard Bartenieff – Icon of Possibility.”