In Meaning in Motion, I explain that Laban’s notion of the mover’s space has two aspects: one descriptive and one prescriptive.

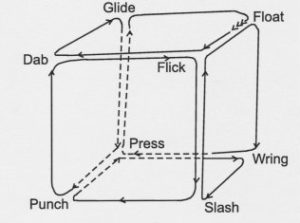

To better describe movement, Laban created several “geographies” of space. These give definition to the bubble of territory adjacent to the mover’s body, which Laban called the “kinesphere.” Such geographies created landmarks in the kinesphere and make the systematic description of motion in three dimensions possible.

In addition, Laban designed highly symmetrical sequences of directional change that circle through different areas of the kinesphere. These prescribed sequences of directional change provide a way to explore the kinesphere, to test balance, and to expand the range of motion.

Because Laban’s language of space relies upon geometrical models that must be imagined as surrounding the mover’s body, the spatial aspects of Laban Movement Analysis challenges many students. Consequently, in Meaning in Motion I have incorporated many creative explorations. These address the kinesphere; the Dimensional Scale; the planes; oblique mobility and the Diagonal Scale; and central, peripheral, and transverse movement. More advanced spatial sequences are notated in the appendix.

There is a lot of material in this chapter so that instructors can pick and choose what they want to emphasize in a given course. If the language of space speaks to a student, he or she will also be able to see that there is more movement material to be explored.