Laban’s autobiography, A Life for Dance, is a curious book, but one that reveals a great deal about his creative vision and theatrical activities. As he notes in the letter to his publisher that opens the book:

Laban’s autobiography, A Life for Dance, is a curious book, but one that reveals a great deal about his creative vision and theatrical activities. As he notes in the letter to his publisher that opens the book:

“I recount in my book how a human being makes his way through thousands of circumstances and events. Since this person happens to be a dance master or even a dance-poet, the book will frequently speak about the precious little-known art of dance. The whole kaleidoscope of events, both gay and serious, revolves around dance dramas, plays, and festivals which that dance master has invented.”

Laban wrote the book in the early 1930s, after an injury ended his performance career. It is a summing up of his own career in dance, and in that sense, a kind of farewell. On the other hand, the third part of the book goes beyond the personal to address the roles that dance might play in contemporary social and cultural life. Thus the book also looks forward.

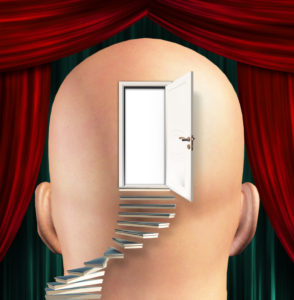

Laban is particularly hopeful about what he calls dance-drama – a “completely novel dramaturgy” that “leads to a new perception of life which tells us of the inner path taken by a character.” The dynamic and partially abstract nature of dance moves beyond being merely a representational narrative of characters and events. As Laban writes:

“Merely to witness incidents does not force us to look too deeply into the nature of events. Only the portrayal of the peculiar fusion of spiritual nobility and human passion which sets external happenings in motion compels us to experience that kind of involvement through which we come nearer to the deeper meaning of experience.”

Laban’s own dance-dramas often involved fairy tale figures, historical characters, or archetypes such as “joygrief,” “lovehate,” and death. His work was not meant to be escapist, however. Rather, “it is a turning to reality, where the meaning of the development of the hero’s true being is found, both in his nature and in the experience of his inner struggles.” As he notes, “in the characters of a military leader such as Agamemnon, a Don Juan, a Savonarola, or in the comic and tragi-comic figures of a jester, a Casanova, and other historical and archetypal personages, I saw not so much the victims of fate, but more the embodiments of ethical values and attitudes.”

Thus his later work, Mastery of Movement, is not just about the acquisition of theatrical skills. It speaks more deeply to mastery of a dynamic self –one that is not only bound to respond to events out of habit, but also capable to transcending habitual reactions by means of humane effort.

One challenging aspect of Laban’s Mastery of Movement is his description of many dramatic scenes meant to be embodied by the reader. These scenes involve multiple characters, various dramatic conflicts, and several changes in mood on the part of all the characters involved.

One challenging aspect of Laban’s Mastery of Movement is his description of many dramatic scenes meant to be embodied by the reader. These scenes involve multiple characters, various dramatic conflicts, and several changes in mood on the part of all the characters involved. In Mastery of Movement, Rudolf Laban invokes gods, goddesses, and demons in his discussions of the “chemistry of human effort.”

In Mastery of Movement, Rudolf Laban invokes gods, goddesses, and demons in his discussions of the “chemistry of human effort.” Laban’s life work was to create a rich palette of movement options from which a performer could draw. By the time he wrote Mastery of Movement, he had a lifetime of experience observing movement and working with dancers and actors, which he distilled into this intriguing work.

Laban’s life work was to create a rich palette of movement options from which a performer could draw. By the time he wrote Mastery of Movement, he had a lifetime of experience observing movement and working with dancers and actors, which he distilled into this intriguing work. I have been re-reading Laban’s autobiography in preparation for teaching

I have been re-reading Laban’s autobiography in preparation for teaching  Laban wrote Mastery of Movement on the Stage (1st edition) “as an incentive to personal mobility.” And indeed, the first two chapters provide a number of explorations organized around movement themes focused on body and/or effort. Laban hopes to encourage a kind of “mobile reading,” as he explains in the Preface.

Laban wrote Mastery of Movement on the Stage (1st edition) “as an incentive to personal mobility.” And indeed, the first two chapters provide a number of explorations organized around movement themes focused on body and/or effort. Laban hopes to encourage a kind of “mobile reading,” as he explains in the Preface. Long before diversity became a political issue, Warren Lamb was encouraging diversity in management teams. His model of diversity was not based on age, race, creed, or gender. Rather it was based on decision-making style.

Long before diversity became a political issue, Warren Lamb was encouraging diversity in management teams. His model of diversity was not based on age, race, creed, or gender. Rather it was based on decision-making style. Shortly after I completed my Laban Movement Analysis training (1976), Warren Lamb gave a short course at the Dance Notation Bureau. I had been thinking a lot about the relationship between movement and psychology, but in vague and hypothetical ways. What Lamb presented was much more concrete — it blew me away.

Shortly after I completed my Laban Movement Analysis training (1976), Warren Lamb gave a short course at the Dance Notation Bureau. I had been thinking a lot about the relationship between movement and psychology, but in vague and hypothetical ways. What Lamb presented was much more concrete — it blew me away. In 2011, I participated in a pilot study examining the validity of Movement Pattern Analysis profiles in predicting decision-making patterns. Although MPA has been used by senior business teams for over 50 years, its potential application to the study of military and political leaders has barely been tapped. The pilot study was the first test of this new area of application.

In 2011, I participated in a pilot study examining the validity of Movement Pattern Analysis profiles in predicting decision-making patterns. Although MPA has been used by senior business teams for over 50 years, its potential application to the study of military and political leaders has barely been tapped. The pilot study was the first test of this new area of application.