Laban wrote Mastery of Movement on the Stage (1st edition) “as an incentive to personal mobility.” And indeed, the first two chapters provide a number of explorations organized around movement themes focused on body and/or effort. Laban hopes to encourage a kind of “mobile reading,” as he explains in the Preface.

Laban wrote Mastery of Movement on the Stage (1st edition) “as an incentive to personal mobility.” And indeed, the first two chapters provide a number of explorations organized around movement themes focused on body and/or effort. Laban hopes to encourage a kind of “mobile reading,” as he explains in the Preface.

However, he also notes that there is something in the book for those who want to remain in a comfy chair. That is, such readers can learn more about “thinking in terms of movement.” For Laban, mobile thinking is not merely “cavorting in the world of ideas” any more than stage movement is “restricted to ballet.” And herein Laban reveals his broader theme: movement “forms the common denominator to both art and industry.”

In the Preface, Laban also makes it quite clear that movement is not merely a physical practice that can be mastered through mechanical exercises. Movement involves the “inner life of man.” For genuine mastery, the motivation to move must be integrated with the acquisition of external skill.

Laban also establishes his views on theatre, noting that the stage is “the mirror of man’s physical, mental, and spiritual existence.” And in the Introduction, he goes on to assert that movement is the heart of theatre, for there is no acting, speaking, singing, or dancing without movement.

In many ways, Mastery of Movement is a quintessential representation of Laban’s vision, which illuminates details of bodily activity and yet broadly positions the whole experience of movement in relation to human existence in the world of both tangible and intangible values.

Find out more in the upcoming correspondence course, Mastering Rudolf Laban’s Mastery of Movement.

I may think the Denver Art Museum’s “Summer of Dance” is splendid, but the Denver Post’s critic disagrees. He writes, “As a theme, ‘dance’ is, frankly, thin, a fringe topic that’s wholly without risk and lacks the kind of gravitas that a serious museum has the skill and resources to tackle.” Other phrases are similarly dismissive: “escapism,” “light touch,” “fun,” and finally, in response to the display of Anna Pavlova’s tutu – “This year, its feathery fluffiness feels like a metaphor for the whole lineup at DAM.”

I may think the Denver Art Museum’s “Summer of Dance” is splendid, but the Denver Post’s critic disagrees. He writes, “As a theme, ‘dance’ is, frankly, thin, a fringe topic that’s wholly without risk and lacks the kind of gravitas that a serious museum has the skill and resources to tackle.” Other phrases are similarly dismissive: “escapism,” “light touch,” “fun,” and finally, in response to the display of Anna Pavlova’s tutu – “This year, its feathery fluffiness feels like a metaphor for the whole lineup at DAM.” My home town’s major art museum is hosting four separate exhibits on dance this summer.

My home town’s major art museum is hosting four separate exhibits on dance this summer.  I am happy to announce the publication of Dance’s Duet with the Camera. This collection of essays, edited by Telory D. Arendell and Ruth Barnes and published by Palgrave Macmillan, “takes on the difficult task of verbalizing how the live aspects of present, sweaty, energy-driven dancers might collaborate with the more staid, focused, and digitally manipulated forms of either

I am happy to announce the publication of Dance’s Duet with the Camera. This collection of essays, edited by Telory D. Arendell and Ruth Barnes and published by Palgrave Macmillan, “takes on the difficult task of verbalizing how the live aspects of present, sweaty, energy-driven dancers might collaborate with the more staid, focused, and digitally manipulated forms of either  “Why are we learning this?” Anyone who has ever taught Space Harmony will have heard this question from students. In fact, many Certified Movement Analysts have themselves struggled with this part of Laban’s work. But the study of

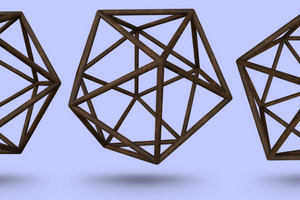

“Why are we learning this?” Anyone who has ever taught Space Harmony will have heard this question from students. In fact, many Certified Movement Analysts have themselves struggled with this part of Laban’s work. But the study of  In July, with the Octa workshop, “Bringing Choreutics to Life,” I took these theories forward into practice. During this intimate three-day workshop, we reviewed well-known Choreutic sequences to illuminate their rational structure and to explore how Laban’s ideas can be transformed into rich kinesthetic and expressive experiences, integrating body and mind.

In July, with the Octa workshop, “Bringing Choreutics to Life,” I took these theories forward into practice. During this intimate three-day workshop, we reviewed well-known Choreutic sequences to illuminate their rational structure and to explore how Laban’s ideas can be transformed into rich kinesthetic and expressive experiences, integrating body and mind.