When I first studied Laban Movement Analysis with Irmgard Bartenieff, I was in my early 20s and she was in her mid-70s. Like all of the other young students, I regarded her with a certain amount of awe.

Irmgard had an extraordinary resume. Not only had she studied with Rudolf Laban in Germany in the fertile and exciting 1920s, she had gone on to work as a movement professional in an amazing array of fields – dance, physical therapy, visual anthropology, child development research, and dance/movement therapy. She had managed to make contributions in these fields despite having to escape from the Nazi regime, immigrate to the United States with her family, and make her way in a different land and language.

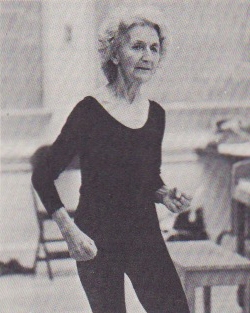

Irmgard had the gift of being old without ever seeming elderly. Students and faculty alike looked up to her as an authority, but not because she ever stood on her laurels. Quite the contrary. She embraced change. Although her life had been both rich and difficult, Irmgard was not oriented to the past. She always looked forward.

Irmgard managed to give her students and colleagues the sense that we were standing on the threshold of an uncharted territory, one in which we, too, could make discoveries. Few people could appreciate the complexity of studying human movement as Irmgard did. As Marcia Siegel put it, “She thought mind, body, and action are one, that the individual is one with the culture, and function with expression, space with energy, art with work with environment with religion.”

Irmgard’s global vision human movement could confuse students who wanted answers in neat compartments. However, her greatest gift as a teacher was not to give pat answers but to suggest possibilities and connections. For, as Siegel notes, once you had worked with Irmgard, “you could never again see the universe as a collection of isolated particles.”