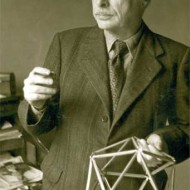

Another example of Laban’s double vision is his concept of the kinesphere and dynamosphere as dual domains of human movement. To represent both domains, Laban utilizes the cube.

With regard to the kinesphere, Laban uses the cube quite literally. Its corners, edges, and internal diagonals serve as a kind of longitude and latitude for mapping movement in the space around the dancer’s body.

With regard to the dynamosphere, Laban uses the cube formally to represent patterns of effort change. This shift in how the model should be interpreted is complicated further by Laban’s use of direction symbols to stand for effort qualities and combinations.… Read More