(This excerpt is taken from my book, The Harmonic Structure of Movement, Music, and Dance According to Rudolf Laban.)

As noted earlier, Laban initially perceived two fundamental psychological attitudes: one of resisting or fighting the physical conditions influencing movement, the other of yielding and accepting these conditions. These attitudes were used in the construction of bi-polar qualities for each of the four motion factors. In later years, Laban hypothesized correlations between these four motion factors and the four functions of consciousness theorized by Jung: sensing, thinking, feeling, and intuiting. Jung used these constructs to develop a dense theory of personality type in which each function is modified by many other psychological factors such as attitudes or extraversion or introversion, conscious development or unconscious regression, and so on. Put simply, however, Jung explained the four functions as follows: “Sensation (i.e. sense-perception) tells you that something exists; thinking tells you what it is; feeling tells you whether it is agreeable or not; and intuition tells you whence it comes and where it is going.”

To elaborate, the function of sensing has to do with the perception of what is tangible and palpable in the immediate environment. Laban associated this perceptive function with the motion factor of weight and the intent to apply pressure firmly or delicately. As Katya Bloom puts it, weight “relates to the physical-sensory world, the actual material substance of the body, and the sense of touch.”

The function of thinking has to do with rational judgment based upon the analysis and classification of sensory data in relation to ideas and concepts. Laban associated this function with the motion factor of space and the effort exerted to orient oneself directly or flexibly in the environment. According to Bloom, space relates to “one’s point of view on the outside world. It implies a space for reflection and thought, and is therefore related to the mind, to the mental aspect of experience.”

The function of feeling allows one to establish what one likes and what one dislikes and this judgment is often experienced as a visceral reaction of attraction or repulsion, pleasure or pain. Laban associated feeling with the motion factor of flow and the effort to move with fluid abandon or to hold motion in check. Bloom sees the control or release of tension as analogous to “the control or release of feelings” and relates flow to “the experience of emotion in the body.”

Finally, the function of intuition has to do with sudden perceptions and insights that seemingly do not arise from immediate sense perception or methodical reasoning. Laban associated this function with the motion factor of time. Here Laban seems to be drawing on Henri Bergson’s idea that intuition is the direct apprehension of a “living time” that is experienced “from within.” Living time does not move smoothly at a steady rate: some hours fly by, while other hours creep. Laban appears to see the decisive effort to speed up or slow down as arising from this internal, hence “intuitive” sense of timing.

Learn more about the psychology of movement at the upcoming Octa Seminar, August 7-9, 2014. Register now.

Balance plays a significant role in Rudolf Laban’s thinking. This emphasis is understandable. As I note in

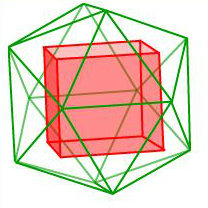

Balance plays a significant role in Rudolf Laban’s thinking. This emphasis is understandable. As I note in  As Laban conceived them, the dynamosphere and kinesphere are parallel movement territories. They share many characteristics. For example, Laban created three-dimensional geometrical models for both spheres. These models allow him to map both the movement from place to place and the movement from mood to mood, capturing both the physical and emotional characteristics of human actions.

As Laban conceived them, the dynamosphere and kinesphere are parallel movement territories. They share many characteristics. For example, Laban created three-dimensional geometrical models for both spheres. These models allow him to map both the movement from place to place and the movement from mood to mood, capturing both the physical and emotional characteristics of human actions.