In 1991, Charlotte Honda, Kaoru Yamamoto, and I formed Motus Humanus, a professional organization for Laban-based movement specialists. Over Labor Day weekend, we celebrated our 25th anniversary in Santa Fe, New Mexico, with over 30 movement analysts and invited guests.

In 1991, Charlotte Honda, Kaoru Yamamoto, and I formed Motus Humanus, a professional organization for Laban-based movement specialists. Over Labor Day weekend, we celebrated our 25th anniversary in Santa Fe, New Mexico, with over 30 movement analysts and invited guests.

“Six Conversations about Human Movement” provided the theme for this, our 8th Roundtable on Professional Issues. In this unique event, each of our six volunteer Board members (David Bauer, Cate Deicher, Alison Henderson, Becky Nordstrom, Kaoru Yamamoto, and myself) invited a special guest for a chat. Six stimulating exchanges resulted on a variety of topics.

David Bauer and Mindfulness instructor Steve Flowers discussed “Mindful Paths to Healing Our Minds and Bodies in Post-Modern Culture,” Cate Deicher and philosopher Amy Shapiro explored “Thinking Movement/Moving Thought,” Alison Henderson and British movement-for-actors specialist Juliet Chambers-Coe shared their experiences with “LMA and the Role of Movement in Theatre Training,” Becky Nordstrom and choreographer Claire Porter had “A Conversation about Moving while Moving,” Kaoru Yamamoto and dancer/martial artist Charlotte Honda discussed “Human Movements: Varying Points of View and Life Courses,” and Waldorf educator Robert Schiappacasse and I compared the careers and aims of Rudolf Steiner and Rudolf Laban in “Spirited Forms – Art, Individuality, and Impulses for a New Age.”

Many of these conversations incorporated movement experiences, including a wonderful performance of “Happenstance” by Claire Porter. In addition, there were morning movement sessions led by Charlotte Honda (Tai Chi), Becky Nordstrom (improvisational explorations of reach space and indulging effort qualities), and Claire Porter (dance composition techniques combining movement and words).

The gathering provided an occasion to honor loyal members and reflect on the organization’s service to the field of movement analysis. Find out more in the next blogs.

In 1975 Buckminster Fuller coined the term “tensegrity” by contacting two terms — tensional and integrity. Simply defined, tensegrity refers to “compression elements in a sea of tension.”

In 1975 Buckminster Fuller coined the term “tensegrity” by contacting two terms — tensional and integrity. Simply defined, tensegrity refers to “compression elements in a sea of tension.” I may think the Denver Art Museum’s “Summer of Dance” is splendid, but the Denver Post’s critic disagrees. He writes, “As a theme, ‘dance’ is, frankly, thin, a fringe topic that’s wholly without risk and lacks the kind of gravitas that a serious museum has the skill and resources to tackle.” Other phrases are similarly dismissive: “escapism,” “light touch,” “fun,” and finally, in response to the display of Anna Pavlova’s tutu – “This year, its feathery fluffiness feels like a metaphor for the whole lineup at DAM.”

I may think the Denver Art Museum’s “Summer of Dance” is splendid, but the Denver Post’s critic disagrees. He writes, “As a theme, ‘dance’ is, frankly, thin, a fringe topic that’s wholly without risk and lacks the kind of gravitas that a serious museum has the skill and resources to tackle.” Other phrases are similarly dismissive: “escapism,” “light touch,” “fun,” and finally, in response to the display of Anna Pavlova’s tutu – “This year, its feathery fluffiness feels like a metaphor for the whole lineup at DAM.” My home town’s major art museum is hosting four separate exhibits on dance this summer.

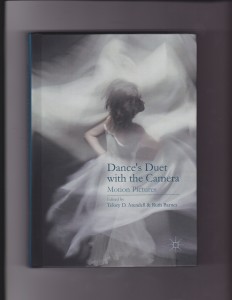

My home town’s major art museum is hosting four separate exhibits on dance this summer.  I am happy to announce the publication of Dance’s Duet with the Camera. This collection of essays, edited by Telory D. Arendell and Ruth Barnes and published by Palgrave Macmillan, “takes on the difficult task of verbalizing how the live aspects of present, sweaty, energy-driven dancers might collaborate with the more staid, focused, and digitally manipulated forms of either

I am happy to announce the publication of Dance’s Duet with the Camera. This collection of essays, edited by Telory D. Arendell and Ruth Barnes and published by Palgrave Macmillan, “takes on the difficult task of verbalizing how the live aspects of present, sweaty, energy-driven dancers might collaborate with the more staid, focused, and digitally manipulated forms of either  In addition to developing physical skills, Choreutic practice also challenges movers intellectually. It gives us a way to think about space.

In addition to developing physical skills, Choreutic practice also challenges movers intellectually. It gives us a way to think about space. “Why are we learning this?” Anyone who has ever taught Space Harmony will have heard this question from students. In fact, many Certified Movement Analysts have themselves struggled with this part of Laban’s work. But the study of

“Why are we learning this?” Anyone who has ever taught Space Harmony will have heard this question from students. In fact, many Certified Movement Analysts have themselves struggled with this part of Laban’s work. But the study of  by Kathie Debenham

by Kathie Debenham by Laurie Cameron

by Laurie Cameron In the Vaccination Theory of Education, students are led to believe that once they have “had” a subject, they are immune to it and need not take it again.

In the Vaccination Theory of Education, students are led to believe that once they have “had” a subject, they are immune to it and need not take it again.