I may think the Denver Art Museum’s “Summer of Dance” is splendid, but the Denver Post’s critic disagrees. He writes, “As a theme, ‘dance’ is, frankly, thin, a fringe topic that’s wholly without risk and lacks the kind of gravitas that a serious museum has the skill and resources to tackle.” Other phrases are similarly dismissive: “escapism,” “light touch,” “fun,” and finally, in response to the display of Anna Pavlova’s tutu – “This year, its feathery fluffiness feels like a metaphor for the whole lineup at DAM.”

I may think the Denver Art Museum’s “Summer of Dance” is splendid, but the Denver Post’s critic disagrees. He writes, “As a theme, ‘dance’ is, frankly, thin, a fringe topic that’s wholly without risk and lacks the kind of gravitas that a serious museum has the skill and resources to tackle.” Other phrases are similarly dismissive: “escapism,” “light touch,” “fun,” and finally, in response to the display of Anna Pavlova’s tutu – “This year, its feathery fluffiness feels like a metaphor for the whole lineup at DAM.”

As a dancer, it is difficult for me to see this merely as a criticism of the museum’s exhibitions – it seems to be a denunciation of dance itself. In this critic’s eyes, at least, dance is ornamental, trivial, light weight — an art that lacks “gravitas.” While I may disagree, I fear this writer’s views are reflective of more general public perceptions of the nature and value of dance.

Over a hundred years ago, when the painter Rudolf Laban decided to pursue dance, he confessed that he felt he had set his heart on “the most despised profession in the world.” Dance may no longer be regarded as a profane or disreputable enterprise, but its profound value, its “gravitas,” has yet to be appreciated by art critics and the general American public.

The United States is not a dancing culture. Yes, we have popular dance, theatrical dance, even competitive dance on television. But most people do not participate in dancing on any regular basis. In my view, dance is meant to be done. Its value and meaning are only revealed through the experience of doing it. Seeing is nice, but dance should not be merely a theatrical spectacle and certainly not a competitive sport.

Until we find a way to embed dance in the lives of everyday people, dance will continue to be dissed and dismissed as a fringe topic – feathery, fluffy, fun — and largely without serious value.

“You must not think of dance as steps,” Rudolf Laban once told a group of student actors. “Dance is meaningful movement. You can dance with your eyebrows. When I have taught you, you will be able to dance with any part of your body.’’

“You must not think of dance as steps,” Rudolf Laban once told a group of student actors. “Dance is meaningful movement. You can dance with your eyebrows. When I have taught you, you will be able to dance with any part of your body.’’

Lamb affirmed that “effort goes with shape organically.” Yet careful study of an individual’s movement pattern will reveal an emphasis on effort more than shape, or vice versa. Lamb came to feel that this difference was fundamental and significant.

Lamb affirmed that “effort goes with shape organically.” Yet careful study of an individual’s movement pattern will reveal an emphasis on effort more than shape, or vice versa. Lamb came to feel that this difference was fundamental and significant.

Rudolf Laban’s use of movement-based observational techniques anticipated the notion of “embodied cognition” by several decades. In his writings in the 1940s and 50s, Laban already had identified “mental efforts” — namely those of giving attention to what must be done, forming an intention to act, and finally taking decisive action — as stages of “inner preparation for outer action.”

Rudolf Laban’s use of movement-based observational techniques anticipated the notion of “embodied cognition” by several decades. In his writings in the 1940s and 50s, Laban already had identified “mental efforts” — namely those of giving attention to what must be done, forming an intention to act, and finally taking decisive action — as stages of “inner preparation for outer action.” Over the past six years, I have been part of an interdisciplinary research team testing Movement Pattern Analysis (MPA). The team consists of movement analysts, political scientists, and psychologists. We have been comparing the Movement Pattern Analysis profiles of a participant group of military officers with their performance on a set of decision-making tasks completed in a laboratory situation. Our aim is to assess how well their MPA profiles correlate with their decision-making behaviors in the lab.

Over the past six years, I have been part of an interdisciplinary research team testing Movement Pattern Analysis (MPA). The team consists of movement analysts, political scientists, and psychologists. We have been comparing the Movement Pattern Analysis profiles of a participant group of military officers with their performance on a set of decision-making tasks completed in a laboratory situation. Our aim is to assess how well their MPA profiles correlate with their decision-making behaviors in the lab. Laban wrote Mastery of Movement on the Stage (1st edition) “as an incentive to personal mobility.” And indeed, the first two chapters provide a number of explorations organized around movement themes focused on body and/or effort. Laban hopes to encourage a kind of “mobile reading,” as he explains in the Preface.

Laban wrote Mastery of Movement on the Stage (1st edition) “as an incentive to personal mobility.” And indeed, the first two chapters provide a number of explorations organized around movement themes focused on body and/or effort. Laban hopes to encourage a kind of “mobile reading,” as he explains in the Preface. I may think the Denver Art Museum’s “Summer of Dance” is splendid, but the Denver Post’s critic disagrees. He writes, “As a theme, ‘dance’ is, frankly, thin, a fringe topic that’s wholly without risk and lacks the kind of gravitas that a serious museum has the skill and resources to tackle.” Other phrases are similarly dismissive: “escapism,” “light touch,” “fun,” and finally, in response to the display of Anna Pavlova’s tutu – “This year, its feathery fluffiness feels like a metaphor for the whole lineup at DAM.”

I may think the Denver Art Museum’s “Summer of Dance” is splendid, but the Denver Post’s critic disagrees. He writes, “As a theme, ‘dance’ is, frankly, thin, a fringe topic that’s wholly without risk and lacks the kind of gravitas that a serious museum has the skill and resources to tackle.” Other phrases are similarly dismissive: “escapism,” “light touch,” “fun,” and finally, in response to the display of Anna Pavlova’s tutu – “This year, its feathery fluffiness feels like a metaphor for the whole lineup at DAM.” My home town’s major art museum is hosting four separate exhibits on dance this summer.

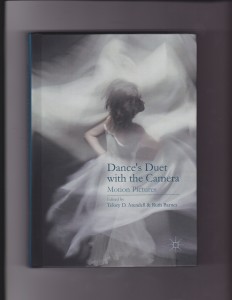

My home town’s major art museum is hosting four separate exhibits on dance this summer.  I am happy to announce the publication of Dance’s Duet with the Camera. This collection of essays, edited by Telory D. Arendell and Ruth Barnes and published by Palgrave Macmillan, “takes on the difficult task of verbalizing how the live aspects of present, sweaty, energy-driven dancers might collaborate with the more staid, focused, and digitally manipulated forms of either

I am happy to announce the publication of Dance’s Duet with the Camera. This collection of essays, edited by Telory D. Arendell and Ruth Barnes and published by Palgrave Macmillan, “takes on the difficult task of verbalizing how the live aspects of present, sweaty, energy-driven dancers might collaborate with the more staid, focused, and digitally manipulated forms of either  In addition to developing physical skills, Choreutic practice also challenges movers intellectually. It gives us a way to think about space.

In addition to developing physical skills, Choreutic practice also challenges movers intellectually. It gives us a way to think about space.